Description

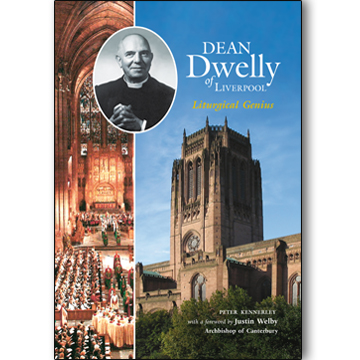

Dean Dwelly ‘s creativity in the use of poetry, of music, of the commissioning of art, and in the use of the Great Space of Liverpool Cathedral set him apart from his peers and therefore won huge admiration from all quarters. Above all, his liturgy was always centred around the value of the human being and he fostered worship that was dignified, imaginative and relevant for the thousands of people who attended services.

A must for all those interested in Liverpool’s history. Lavishly illustrated in full colour throughout.

- Author: Peter Kennerley, with a foreword by the Archbishop of Canterbury

- Imprint: Palatine Books

- ISBN: 978-1-910837-02-3

- Binding: Softback

- Pages: 320

- Published: 2015

Jane Kennedy, Anaphora 11.2 (2017) pp.77–93 –

In this beautifully illustrated book the significance of Frederick William DweIly (1881–1957) as priest and reforming liturgist is set against the background of the most exciting cathedral building project of the twentieth century. Archbishop Welby’s introduction gets to the heart of the man:

Dwelly inspired me especially with the two questions he often used to ask people when the planning of a service began. ‘What do you want to say to each other?’ ‘What do you want to say to God?’ These questions…stop what can be a danger in most places…that people become a necessary but inconvenient obstacle to the otherwise enjoyable business of liturgy.

Dwelly was the son of a Somerset coach builder. There is little information about his early life but perhaps his future impact on the Church of England was foreshadowed when, as a chorister – and on 5 November – he set off a large fire cracker inside the church organ. After some falling out with his family and an early career in Marshall and Snelgrove’s department store, he was encouraged to enter Cambridge University with a view to ordination.There he was inspired by Dean Inge, whom he heard speaking on the value of the arts, and how literature, music, painting, statuary and ceremonial could be used to deal with the real issues of the spiritual and natural world without relying on the historical truth, or otherwise, of the gospel stories.

Dwelly’s first curacy was in Windermere where he demonstrated both his organisational skills and his imagination. In his second post, at Cheltenham, the popularity of his preaching drew 2,000 people to his final service, with so many turned away that the sermon had to be repeated. During his first incumbency in Southport in the Liverpool Diocese he became involved in Bishop Randall Davidson’s ‘National Mission of Repentance and Hope’. (That this was a movement of reform, with the aim of disestablishing the Church. shows how long the Anglican Church has used euphemistic titles for its commissions and studies). Dwelly advocated liberty for the Church to grow.He was also employed upon the reform of the Prayer Book from 1923. His work with Percy Dearmer led to the publication of Acts of Devotion, short prayers and responses which still sound clear and contemporary today.

Services at Southport were varied, and exemplified a diversity in forms of worship eighty years before the launch of Common Worship in 2000. In a similarly prescient discussion at a church council meeting and in an article in the parish magazine he argued for the ordination of women:

When one looksout today upon the deplorable state of Christianity in this and every other country, one is driven to the conclusion that what the church needs today is the active ministrations of God-fearing earnest women.

Dwelly was invited to work on the consecration service for Liverpool Cathedral in 1924, whilst still in parish ministry in Southport. He undertook detailed research into historical liturgies to inform the service and masterminded the whole event, remaining calm and unflappable on the day, even when the King and Queen arrived twenty minutes early. Detailed descriptions and numerous extracts from the form of service, while in some cases repetitive, provide a useful source of ideas for anyone planning major services now. The concecration was described in the Sunday Times:

There was majesty and pomp, as befits all Royal Ceremonies; but the atmosphere in the cathedral was one of mysticism, something spiritual and inexplainable, a kind of service which inspired religious worshippers in medieval ages, and yet so adapted that thechurchmen and churchwomen of today found in it comfort and inspiration.

Kennerley, a former EducationOfficer at the cathedral, gives us his own history of the building, setting out its significance in Liverpool as a tventieth-century institution, its architectural design and its provision of spaces for liturgy. He also considers its relationship to the urban context, built on St James’ Mount to overlook the contemporary great commercial buildings of 1910–16: the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board Building, the Royal Liver and Cunard Buildings. The architect was Giles Gilbert Scott (1880–1960), and he and Dwelly were not only contemporaries but also became firm friends.

Following the consecration, Dwelly was appointed to be a residentiary canon and undertook a lecture tour in United States. He worked very successfully with Charles Raven (then a fellow canon but later Regius Professor of Divinity and Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University) and together they Instituted an 8.30 p.m. Sunday service (timed so as not to clash with parish churches). These were experimental services and the seriousness taken in their preparation was observed:

Dwelly would lie flat on one of the great oak tables in the darkened vestry before going in to preach: Raven would pace up and down almost physically sick rehearsing his words and gestures like an actor.

At the behest of Dean George Bell, Dwelly went on to write a service for the consecration of Cosmo Lang as Archbishop of Canterbury. He also advised Archbishop Lang on a Service of Thanksgiving for the King’s health which was broadcast throughout the Empire in 1929. Kennerley describes his organisation and leadership of the first World Scout Jamboree in Liverpool in 1929 and the Lambeth Conference visit to commemorate Liverpool Diocesan Jubilee a year later. For Dwelly, music was central to all he planned. He wrote that he ‘wanted to enable the whole body of the people to be caught up in the stream of worship’. The book includes illustrations of a number of most beautifully designed service sheets by Edward Preston, both graphic designer and sculptor to the cathedral.

Dwelly became Dean of Liverpool in 1931. His creed (and Raven’s) was ‘English Modernism’ as articulated in H.D.A. Major’s English Modernism in 1927:

Modernism consists in the claim of the modern mind to determine what is true, right and beautiful in the light of its own experience, even though its conclusions be in contradiction to those of tradition…The intellectual task of modernism is the criticism of tradition in the light of research and enlarging experience, with the purpose of reformulation and reinterpreting it to serve the needs of the present age.

Dwelly’s attitude to ecumenism and indusivity (mirrored by his Bishop) included invitations to representatives of Free Churches and Greek Orthodox ministers to preach in the cathedral. There was a major controversy in 1933, when the Unitarian scholar D. L. P. Jacks was invited. The Chapter was attacked by both evangelical and catholic wings of the church and by Lord Hugh Cecil for the laity. As Adrian Hastings observed, ‘[i]t was indeed the lay Tory control of the Church Assembly which ensured that no odd outburst of some liberal cleric should unduly disturb the policies of the Establishment’ (History of English Christianity 1920–1980, London 1996).

During the war Dwelly lived in the cathedral in a turret, along with the musicians and clerk of works. He helped to free internees and organised major services with the Navy.

Kennerley tells us little of Dwelly’s personal life. We are told that he resigned through ill health in 1955 and died two years later. A ‘Mrs Dwelly’ is referred to after his death and there is a touching account of his long-serving secretary. Although there are intriguing and fleeting images of a jovial man who performed conjuring tricks for Percy Dearmer’s children and arrived at Christmas with sacks of presents for the Raven offspring, there is no vivid account of his domestic life and relationships.

In the absence of a fully rounded picture of Dean Dwelly, Kennerley does however give us clear view of his approach to liturgy and all of the modern Anglican ideas that he espoused. This book is to be commended to all those who want to design effective and profound cathedral and parish services.