Description

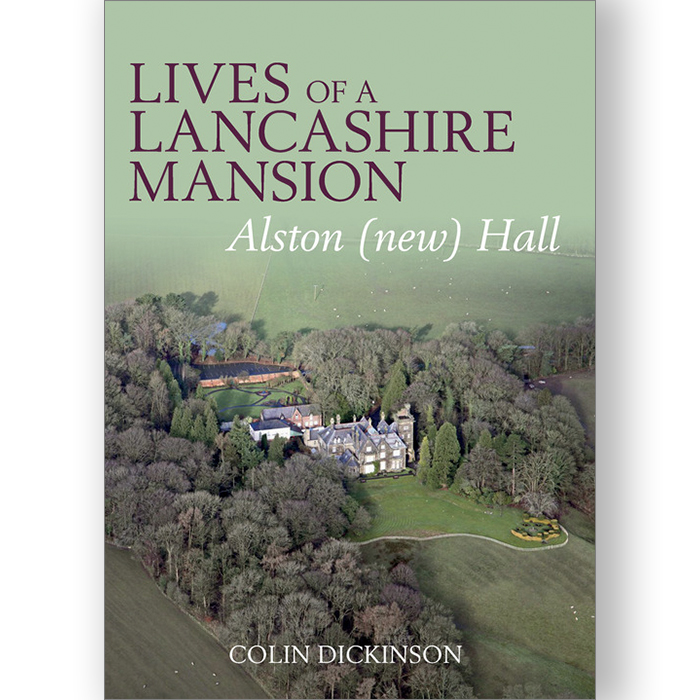

Six years in the making, this superbly crafted book is a ‘must read’ for anyone interested in Victorian country mansions with regard to social life, architecture, layout of rooms and grounds, décor and furniture, twentieth-century developments in electric lighting and vacuum cleaning systems.

The author, with much thoroughness, presents a detailed historical account of one of Lancashire’s well-loved country mansions; an account enriched by a large and impressive selection of illustrations.

In 1954 he began a career in the aircraft industry to work in Preston, Samlesbury and finally Warton, leaving in 1963 to enrol on a one-year technical teacher- training course in Bolton, following which, school-based, he taught physics, mathematics and technical drawing. In 1979 he graduated with a Master of Science degree after a one-year programme of research at the University of Manchester’s Institute of Science and Technology. On retirement, after a long teaching career, he introduced and tutored courses in Victorian and Edwardian architecture as well as industrial archaeology for the Department of Continuing Education at Lancaster University, eventually presenting similar courses at Alston Hall College.

In 1984 Lancashire County Council Library and Leisure Committee published his Lancashire under Steam – the era of the steam-driven cotton mill, and in 2002 Carnegie Publishing Ltd published his Cotton Mills of Preston – the Power Behind the Thread.

- Author: Colin Dickinson

- Imprint: Palatine Books

- ISBN: 978-1-910837-48-1

- Binding: paperback

- Format: 240 x 170mm

- Extent: 380 pages

- Illustrations: 150+

- Audience: GENERAL

- Publication date: 15 January 2024

Terry Wyke –

Originally published in North West Labour History Society Journal no.50.

Alston Hall continues to attract historians. Colin Dickinson’s new history follows in the footsteps of Marian Roberts and Alan Crosby whose accounts of the house were published in 1994 and 2017 respectively. This is surprising given that it is not a house that would find a place in many people’s list of Lancashire buildings of significant historical or architectural interest. Built for wealthy colliery owner John Mercer, it was designed by the Manchester architect Alfred Darbyshire who today is best remembered for his theatre buildings. It was a suitably impressive late Victorian pile, Dickinson providing a detailed description of the building and its rooms. Of these the most revealing is the private chapel, reflecting the family’s strong Catholic faith. The Mercers were well-known supporters of new churches in the Liverpool diocese, including Our Lady’s Immaculate at Bryn close to Mercer’s Parkside collieries. Other members of the family who were to live in the house included Canon James Taylor who shared an interest with Mercer in the breeding of shire horses, carthorses remaining an essential if rather overlooked part of a fast-changing transport economy.

During the First World War the mansion passed out of the hands of King Coal into those of King Cotton, becoming the home of one of Lancashire’s wealthiest cotton manufacturers, William Birtwistle, the owner of mills in Blackburn, Preston, Darwen and other towns. He was a powerful but independent individual in the industry who became a figure of interest in the popular press when in his seventies he married his typist who was in her twenties. He appears to have lived in the hall for only a few years before it was occupied by John Marsden who managed Birtwistle’s extensive business interests. Marsden’s lifestyle was far removed from the time in the 1880s when he had started work as a half-timer in one of Birtwistle’s mills. Of course, the collapse in the cotton industry in the interwar years challenged the Birtwistle family and by the time of his death the fortune of a man who had once been spoken of as a multi-millionaire had been severely reduced.

After the Second World War Preston Council bought the house to be part of its dynamic and forward-looking educational system, eventually becoming a residential college for continuing education. By the 1980s the long fight to defend adult education services was on, and it is to the credit of the education authority that it was not until 2015 that the college was finally closed. It was quickly sold off, passing into the hands of an Asian family who set about restoring the house, an ambitious project that became even more expensive following a disastrous fire.

Dickinson provides a detailed narrative of these changes to the building and its occupants, though readers of this journal would also have been interested in hearing more about, for example, working conditions and labour relations in Mercer’s collieries and Birtwistle’s weaving sheds. Ian Winstanley’s researchers would have pointed the way here, not least into the fatal accidents at Mercer’s High Brook colliery. Readers might also have expected a longer consideration of where the hall’s parvenu owners fitted into the county’s landed society, families whose power, influence and social standing was being challenged in these decades.